A problem of photo enforcement is that it encourages optimization of efficiency of collecting fines as opposed to justice. In my experience, these systems have almost invariably led to a culture of enforcement and prosecution based on the bottom line, with protecting the innocent becoming only an afterthought.

Background

Supporters of these systems contend that cameras are cheaper and more efficient than employing officers to do the same job. They figure that a wizard in a box will never be wrong and we can somehow achieve 100% enforcement, with no collateral victims. With this mindset, it follows that any person who contests a ticket is simply a wrongdoer looking for a loophole to escape responsibility. If such a wrongdoer wants to fight his ticket, the logic goes, the odds should be stacked against him. All of that innocent until proven guilty stuff the founding fathers worried about is no longer important when we have a wizard in a box with perfect accuracy. Further, it costs money to run the courts, so if a wrongdoer wants to present his case in court, it seems only fair that he should shoulder the cost to contest.

The problem: there is no wizard. The systems do make mistakes. I’ve personally been the recipient of two such mistaken citations. The first showed another man in another vehicle altogether. The second was issued in violation of French law and clearly shows me driving below the speed limit. Here I will describe both in terms of costs to the defendant.

Citation #1: Scottsdale, Arizona

The first ticket was dismissed eventually, but not before a couple weeks of shenanigans. First, I wasted a couple hours of my vacation talking to the judge and then meeting with the prosecutor. The prosecutor agreed to a dismissal, but also accused me of wasting her time. Unfortunately her office made a mistake on the paperwork so I received a letter the following week from the court informing me of my new court date. I called the prosecutor and eventually this was all fixed, but not without significant stress and time on my part at a time when I was already in the midst of a big move from Ohio to Iowa. Because of all the legal maneuvering, I ended up with 20-something entries on my criminal background check, which will now be visible to potential employers, etc., even though I was not at all involved in the alleged offense (and the prosecutor’s office agrees). I understand that the records are generated automatically when dealing with a court, but I figured I should have some ability to get them expunged given that this was all because of a simple mistake. However, the court in Scottsdale has a policy not to expunge these tickets (I really don’t get the rationale here). So in the end, the City of Scottsdale is libeling me in perpetuity, for objecting to being charged with a crime I did not commit and for which they had zero evidence.

But the city of Scottsdale’s libel didn’t start there. It turns out that some companies have longstanding freedom of information act requests for all photo citations. For this reason, when I found the ticket in my pile of mail, it was surrounded by advertisements for how to beat my ticket. I generally support freedom of information. In fact, I successfully fought the Ames Police Department when they violated such laws. But, this seems like a situation where my personal information should have been redacted. More importantly, while the correct approach to government transparency is beyond the scope of this post, this shows that false citations have a very real impact on defendants’ privacy.

Citation #2: Écully, France

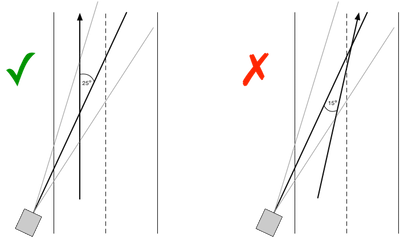

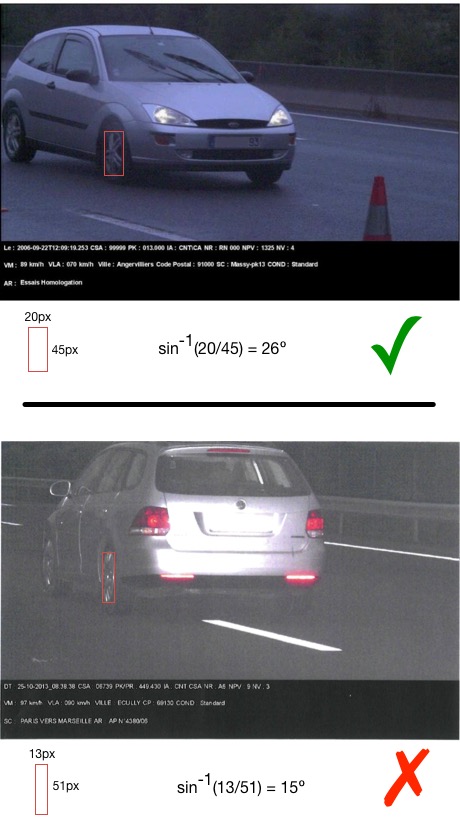

I was found guilty of the second violation, which (allegedly) occurred in France, though hopefully you will read my story because my innocence is really quite apparent. The question of guilt or innocence isn’t really what’s important here. Just note that I had a strong case. This wasn’t some minor point I was arguing. I deserved a proper day in court because I had what many people would agree were reasonable concerns about the accuracy of the ticket. To get this day in court, I had to do the following:

- Pay an additional EUR 53.24 over the base EUR 45.00 fine (total spent = 218% of the base fine). This could have been much, much more. The judge has the ability to increase the fine to approximately eight-fold, but in practice it seems to be a minimum of double the initial fine. If the judge finds your argument unreasonable, you’ll likely get the high end.

- Wait 1.5 years for resolution.

- Write at least five letters (in French) to the authorities. Some went unanswered, including requests for technical details of the radar device that took the photo.

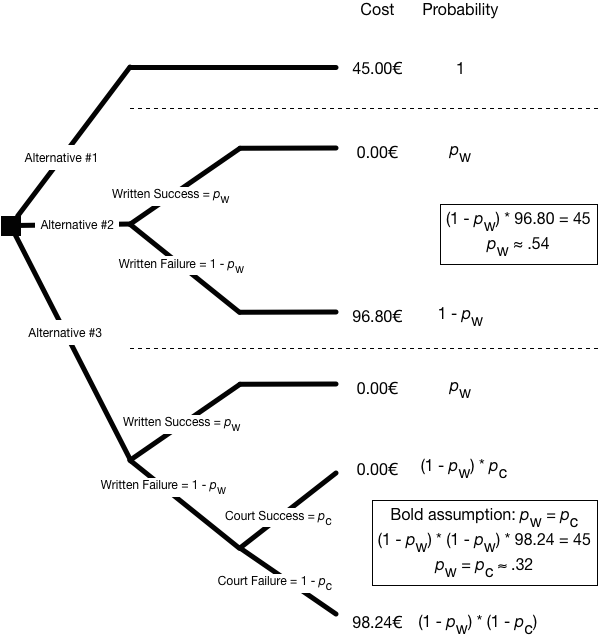

In the following sections, I’ll describe the decision to contest a French ticket in terms of decision theory. I did take a graduate course devoted to this topic, but actually I always found it to be really intuitive. Here is a comprehensive graphic, to be described in the following sections.

Alternative #1: Admit guilt and pay immediately

The first possibility, upon receiving a photo ticket, is to simply pay up. In France, for infractions on roads with a speed limit greater than 50 km/h and with a ticketed speed of less than 20 km/h over that limit, the fine is EUR 45, if paid within 15 days. Bear in mind that this 15-day clock is already started by time you receive the ticket. France does not include photos with the original citation. I suspect this is for two reasons:

- Many people will just assume they broke the law and not consider contesting, but the photo might change their mind.

- Because the French government is

incompetentslower than molasses, it is unlikely that a defendant will receive the original ticket by post and also have time to request and receive the photos by post before the 15-day early payment deadline has passed. Of course it’s not smart to make the decision to contest until you examine the evidence, so this presents a dilemma.

The expected value of choosing this alternative is easy to calculate. There is a 100% chance that you will pay EUR 45.

Alternative #2a: Contest, but only in writing

Granted the decision to proceed to court needn’t be made until a verdict is reached on the written appeal. However, as no new information would generally be available at this later date, there is no value in delaying the decision, meaning that the process can be simplified by assuming you make this decision up front.

The expected value of this alternative can be calculated by multiplying the probability of each outcome by the respective amount paid. Because we do not know the probability of succeeding in court, we cannot solve this in absolute terms. But, we can solve for the success probability above which a rational person will contest. The math shows that a rational person should be willing to contest in writing only if there is greater than a 54% chance of success.

From looking around the internet and from my knowledge of other jurisdictions, I think 54% is very optimistic for a written appeal. It seems that these guys reject almost everything, likely to force defendants to wait another year and proceed to court. Note that I’m not necessarily claiming that the individuals who read the appeals are crooks. In fact, I believe the system is set up by crooks, so that the decision-makers’ options are fairly limited. Also, don’t forget all the normal stuff about how the average person has irrational faith in the wizard who resides in the camera. These people have no real training or incentive to believe you, much less find you innocent.

Alternative #2b: Contest, with willingness to proceed all the way to court

The computation for this final alternative (in fact, there is technically an additional level of appeal, that I won’t cover here) is more involved because the tree has two levels. The best we can do is make the crazy assumption that probability of success on the written appeal equals that in the courtroom. In this case, the math shows that the probability of success must be greater than 32% at each stage for this to be a rational choice (given a willingness/ability to wait 1.5 years).

In reality, the chance of success in the courtroom is likely greater than in writing (and the probabilities are not independent for a given case), but I doubt very much that the win probability in either phase is as high as 32%. Not only can we see my data point, in which I lost even though the camera’s certification was clearly violated, but other anecdotal evidence leads me to believe the chances of success are extremely low in most places in the world (again, irrational belief in wizards, and all that).

The realistic state of freedom in such a system

Of course the calculations above were quite contrived. There is no way to know what your chances are before contesting a ticket using a given argument. This exercise was simply intended to demonstrate the problems with a pay-for-liberté court system.

We can see how they ratchet up the cost at each phase in order to tilt the scales. Given that succeeding in such a trial is extremely rare, unless you actually have a photo of a different car committing the crime, the rational choice is always to just admit guilt and pay. The system is unscrupulous by design, so you would only contest due to strong principles and free cash flow, not because you expect to be vindicated. Poor people don’t really have the liberty of contesting a traffic ticket. I suppose they at least get a free lawyer in extreme circumstances, which undoubtedly helps their chances, but if you barely have enough money to eat would you really want to risk paying twice the original fine?

A fair justice system is only possible if the financial burden is placed on all residents. Deterrents, in the form of financial or other burdens, should be eliminated to the extent possible. Additionally, funding the courts on the backs of losers is a clear conflict of interest. Remember, no safety is gained by collecting fines from innocent drivers.

As a final note, yes I am happy with my choice to fight. The system did lose money on me, which is usually the most you can ask for in modern court systems. I would generally encourage readers to make the same choice.

Leave a Comment